Archives

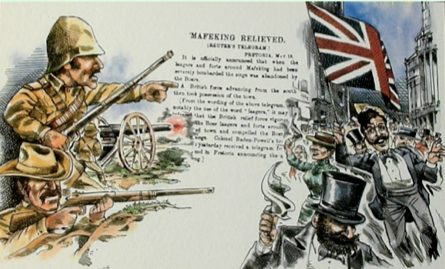

Mafeking relieved!

What a scoop! Londoners went wild with joy. For two and a half days Reuters was alone with the news - so inexplicably alone that some people wondered: Had the infallible Reuters slipped up?

What a scoop! Londoners went wild with joy. For two and a half days Reuters was alone with the news - so inexplicably alone that some people wondered: Had the infallible Reuters slipped up?

There was no mistake. Mafeking, remote outpost in South Africa, besieged from early in the Boer War between the British rulers and Dutch settlers, had been relieved by a flying column of British troops.

For seven months Mafeking had defied the Boers, who controlled all approaches with their strongpoints and laagers, or military camps. The fortunes of the small, tin-roofed township had become the focus of powerful emotions born of the jingoistic national pride of the times and fed by the agonising tension of weeks without news. There were fears of a military disaster.

Then, on May 18, 1900, Reuters issued a laconic message:-

PRETORIA, May 18 (11.35 a.m.)

It is officially announced that when the laagers and forts around Mafeking had been severely bombarded, the siege was abandoned by the Boers. A British force, advancing from the South, then took possession.

A modern ‘flash’ would be slicker, but all the essentials were there, hard news source included. London went stark, raving mad, according to Frederic Dickinson, later Chief Editor, who handled the message. So raving were the celebrations that they could only be described by a new word, ‘mafficking’, which is still in English dictionaries as the verb ‘to maffick’ defined as ‘to celebrate extravagantly’.

It was 9.16 p.m. when a boy appeared in Reuters editorial with a telegram from Lourenço Marques (now Maputo) and handed it to Dickinson.

“I opened it, gave such a yell of delight that everybody knew what the news was, sent the chessmen flying and in two seconds had started the glad tidings on its career round the whole habitable globe,” Dickinson related.

What pleased Reuters most, because it rewarded half a century of painstaking accuracy and self-discipline, was the public confidence, so vigorously expressed, in its news

The chessmen?

Yes. It was a Friday night and news was slack. Dickinson was quietly smoking his pipe and watching others play chess.

Messages went swiftly to Queen Victoria, the Prince of Wales, the Lord Mayor of London, the House of Commons, the Viceroy of India and also to the War Office, which was still without news from its own commanders. The Queen asked for the original telegram and got it, sub-editor’s initials, pencil marks and all.

“By 9.30 an immense crowd, shouting and waving flags, was rushing through the city. How they collected in time is a perfect mystery. The Lord Mayor posted up the news and the newspapers did the same, and it spread like wildfire,” Dickinson wrote to his son.

The Reuter messengers helped spread the news by dashing excitedly about the streets shouting “Mafeking relieved.”

“I walked down to the Press Club with a friend about half past eleven and could hardly get along owing to the packed streets, filled with people dancing, shouting, throwing up hats, blowing trumpets, banging drums and making generally the most frightful row, and I could not help remarking how curious it was that a mild-mannered, elderly gentleman like myself should have been instrumental in setting all this excitement and hubbub going.”

What pleased Reuters most, because it rewarded half a century of painstaking accuracy and self-discipline, was the public confidence, so vigorously expressed, in its news.

Pressed for information in Parliament, Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain told the House he had nothing official, but had every confidence in Reuters accuracy.

Mafeking had been relieved on Thursday and on Sunday Lord Roberts, Commander-in-Chief of British forces in South Africa, read out the Reuter dispatch to troops on church parade in Bloemfontein.

He sent a message to the Secretary of State for War in London saying “No official intimation has as yet been received, but Reuters state that the relief of Mafeking has been effected.” The War Office issued this as an official communiqué.

The Pretoria message that had caused such a sensation reached London only after evading Boer censorship.

Mafeking, commanded by Colonel Robert Baden-Powell, later Lord Baden-Powell and the founder of the Scout movement, was far from any cable station on the British side. The news, however, was quickly known in Pretoria, capital of the Boer republic of Transvaal.

Reuters had a correspondent there, W.H. Mackay, a Scotsman, whose problem was what to do about the censorship. He smuggled his telegram out through Portuguese East Africa (now Mozambique), persuading a train driver to deliver it to the cable office in Lourenço Marques.

Graham Storey, historian of Reuters first 100 years, wrote: “It is said that Mackay had given the engine driver £5 to put the message inside one of his luncheon sandwiches.”

Bon appetit!

■

- « Previous

- Next »

- 5 of 49