Archives

A tale of two cities

Scheunviertel is the name given to the old Jewish quarter of Berlin. It was here, at number 42 Grenadier strasse - home of Clementine’s father, Lutheran pastor Magnus - that we catch up with Julius and Clementine Reuter after the failure of their business trip to London. The date was Spring 1846.

Scheunviertel is the name given to the old Jewish quarter of Berlin. It was here, at number 42 Grenadier strasse - home of Clementine’s father, Lutheran pastor Magnus - that we catch up with Julius and Clementine Reuter after the failure of their business trip to London. The date was Spring 1846.

Why was a Christian Lutheran pastor residing in Grenadier strasse? We don’t know. All we can conclude is that “Jewish quarter” did not mean “exclusively Jewish” and the fact that a Lutheran pastor and his family were also part of the local community was no more unusual than the close proximity in London of Bevis Marks Synagogue and Alie Street Lutheran Church. When Julius Reuter, a rabbi’s son, had first come to Berlin a year or so earlier, it would have been to this district that he made a beeline. With Clementine Magnus already there, we can begin to guess how the couple may first have met.

By the early summer of 1846 Clementine was pregnant with her first child, a daughter, Julie (like Julius, born in July) who, sadly, was to die within a month. The next child of whom we have a record was a boy, born seven years later. During the intervening years, it seems likely that there were further pregnancies and that babies were still-born or quickly died. Such a sad cycle was far from unusual in the mid 19th century. It meant, however, that, unusually, Clementine was left free to play a vital part in her husband’s search for success.

The year 1847 brought with it a new venture. No longer engaged by Reuters Publishing House (although retaining his adopted Reuter surname), and possibly funded by his father-in-law, he became a partner in a Berlin bookshop with one Joseph Stargardt.

The Reuters quit Paris - probably in the middle of the night - leaving their creditors to seize anything worth taking, which wasn't much

Again, things went wrong. Many years later, when Reuters was famously successful, the Stargardt family claimed that he had “flitted” from the 1848 Leipzig Book Fair and kept the firm’s takings of 6,000 thalers (equivalent to £40,000, $56,500 today). Julius Reuter was said to have later offered to repay the money. Whatever the true facts, once again, things had turned to dust. At 32, Clementine’s husband remained what he had always been - a failed businessman, living on hand-outs from his father-in-law.

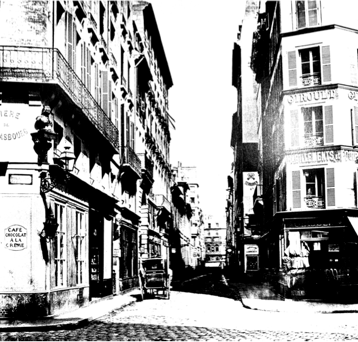

Reuter had one card left to play: his command of German, French and English. So it may have been his language skills which gave him just sufficient edge to be tried out in a completely new field, as sub-editor for the Havas News Agency in Paris. Its owner, 65-year-old Charles-Louis Havas, also Jewish and himself a late-starter, had carved out a new type of business. His agency translated articles from foreign newspapers received in Paris, then sold digests of their contents to local businessmen and to the French government. The Havas office was in the rue Jean-Jacques Rousseau, near to the main Post Office and most subscribers were based within walking distance.

Charles Havas was beginning to explore more ambitious methods whereby, rather than relying upon newspapers, he obtained news directly from his own correspondents on the spot. To assist this, his office was experimenting with carrier pigeons, exploring how this ancient method of communication could be integrated into modern 19th century business. Under discussion will have been possible future applications to which the new electric wonder, the telegraph, could be put. All this Julius Reuter will have absorbed. While working for Havas he will also have come to grasp an important truth for his own future: that news reports were not always accurate, or only gave half the story. It was stock prices which were always the safest of all to handle.

At 33, Reuter was virtually half the age of Havas. For Havas, with a moderately successful business, the urge to develop was not over-riding. As so often happens, the younger man was the hungrier and decided that he could do better on his own. Reuters would be different from Havas in that much greater emphasis would be placed on an outward, rather than an inward service. So each day, Julius and Clementine Reuter sent a bulletin to subscribers back in Germany, meeting the deadline of the 5:00 pm last post at the main Post Office. As well as the Paris Bourse closing prices, they included excerpts from newspaper articles, reports of National Assembly proceedings, general news and - maybe surprising to us today but to pep up the file - a bit of gossip.

Alas, there were just too few subscribers to make the operation viable and by the late summer of 1849 the crash came yet again. The Reuters quit Paris - probably in the middle of the night - leaving their creditors to seize anything worth taking, which wasn’t much.

Somehow the couple scraped together or borrowed enough money for the expensive journey back to long-suffering pastor Magnus in Berlin. Although the couple’s ignominious return to Prussia must have seemed to them their darkest chapter, out if it came the first glimmerings of another opportunity which was to change everything.

In 1849, any traveller from Paris to Berlin was faced with a long journey, involving both the new-fangled steam train and the old-fangled stage coach. A train ran from Paris to Mechelen (Malines) north of Brussels in Belgium, and this connected with another of the very first railway lines which ran as far as Cologne in Prussia. From this point, those wishing to continue on the further 260 miles (420 kilometres) to Berlin, the Prussian capital, had to transfer to the much slower and more-expensive horse-drawn coach.

After at least a day’s journey through France, Belgium and Holland in their uncomfortable railway compartment, the Reuters will have finally crossed the frontier into Prussia. The station on the Prussian side was a busy one and the train will have halted for some considerable time while officials entered each compartment (from the outside; there were no corridors in 1849) to check travel documents. Was it again dark and did the Reuters decide to look for an overnight room in the town? We do not know. But as the locomotive came slowly alongside the platform, enveloped, no doubt, in clouds of steam and smoke, the name of the town which the porters were shouting out was - “Aachen!”.

It was in this Prussian frontier town, not Berlin, Paris (or London) that the fortunes of Julius and Clementine Reuter would at last begin to turn.

PHOTO: A picture dating from about 1860 of rue Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the street in Paris where Charles-Louis Havas had his office. It was from a top floor room further along the same street that Julius and Clementine Reuter operated their short-lived news agency in 1849. ■

- « Previous

- Next »

- 37 of 49