Archives

The new Siamese twins

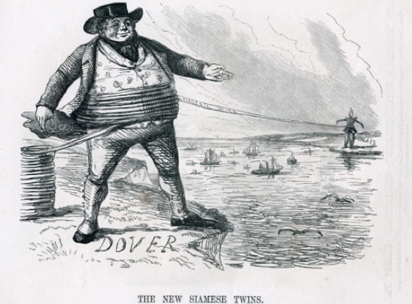

A month after Paul Julius Reuter set up his telegraphic business in London, permanent cross-channel transmissions between Dover and Calais began on 13 November 1851. It seemed that his great gamble that the cable would work successfully had paid off. But, in reality, was the gamble all that great?

A month after Paul Julius Reuter set up his telegraphic business in London, permanent cross-channel transmissions between Dover and Calais began on 13 November 1851. It seemed that his great gamble that the cable would work successfully had paid off. But, in reality, was the gamble all that great?

Reuter has often been said to have based his fledgling new business at 1 Royal Exchange Buildings, London, on a gamble or, at the very least, a calculated risk. He had opened his office on 14 October with the obvious hope that successful telegraphic communication was shortly to be established between England and the rest of Europe via the world’s first undersea cable. It was a gamble that paid off. Was the gamble as much of a deal maker or breaker as it tends now to be portrayed?

Undoubtedly, the hope that cross-channel telegraphic transmissions would soon be an option played a major part in his calculations. The idea that, had the Dover-Calais line failed to work Reuter and his wife Clementine would have packed up and left, never to be heard of again, is probably an over-simplification, however. Attempts to link England and France by cable had already failed twice - in 1847 and in 1850. It was quite possible, therefore, that in 1851 it would fail to work yet again. Even so, Britain’s industrial and commercial supremacy was clear. As the centre of the burgeoning British Empire, London had become the most important city in the world. It was still the place to be. At some stage, fairly soon, a working cable would come into being.

There were no agreed common procedures in those early days of international telegraphy. The handover of messages between different companies and countries, the correction of errors in transmission, the overcoming of line breakdowns and, importantly, the need to bridge gaps in the telegraph network by other means of communication all required special knowledge and agents at central points. Making it a core part of his business, Reuter offered to make paid use of this special expertise on behalf of others. The terminus of the telegraph at Dover and the beginning of the line at Calais was just one more gap which he was ready to bridge. The English Channel was no far-off and dangerous region and if the undersea cable were to continue to fail, none of his London business rivals had access to any alternative. For Reuter, the cable’s absence was quite literally not going to be the end of the world.

Reuter claimed that, as an expert in the use of the telegraph network, he not only obtained the stock market prices before anyone else but was able to collect and make available the widest range of commodity prices

Surviving telegram books for August to October of the following year, 1852, show Reuter at work. He sent short messages for many London merchants and bankers to Antwerp, Hamburg, Trieste, Stettin, Odessa, Danzin and elsewhere in Europe. East European grain prices and prospects, for example, were of particular interest to Greek and other merchants in London, at a period when most of Britain’s grain imports came from the Black Sea area, with Odessa a key outlet. Rothschilds of London used his service to send messages about the sale of stock and related exchange rates. With telegraph charges extremely high - 60 words to Trieste cost £4 17s 6d (almost £300/$470) in today’s values - it was worth employing a specialist.

However, in addition to bespoke services for individual firms, Reuter offered a much cheaper off-the-peg twice-daily relay in each direction of prices on the London Stock Exchange and the Paris Bourse. He also received stock market prices from Brussels, Amsterdam and Vienna, just as he had done when at Aachen. None of this information was exclusive to Reuter and what he charged for it we do not know. Several rival establishments around the Royal Exchange were offering the same data. Reuter claimed that, as an expert in the use of the telegraph network, he not only obtained the stock market prices before anyone else but was able to collect and make available the widest range of commodity prices.

Progress was frustratingly slow. In March 1852, an offer to The Times to supply European stock market prices was firmly - and dismissively - declined by that prestigious newspaper. Nonetheless, five months later, in August, a small chink was made in its armour. By this time, Reuter had managed to secure from Austrian Lloyd of Trieste (formed in 1833 by seven insurance companies along the lines of Lloyd’s of London) the right to circulate onwards that company’s news and market information as received at the Adriatic port of Trieste by ship from the East. Grudgingly, The Times had to look to its own self-interest and, on 17 August, it accepted that it would agree to take “telegraphic news from Trieste” through Reuter’s virtually unknown agency.

The walls had not yet fallen but they had at least begun to crack.

CARTOON: The laying of the Dover-Calais cable depicted in Punch magazine in 1851. ■

- « Previous

- Next »

- 29 of 49