Archives

Reuters' first editor - scoundrel, womaniser and journalist of flair

“One of the great journalists of the day” was how Sigmund Engländer’s contemporaries described him. He was equally well known as a scoundrel and a womaniser.

“One of the great journalists of the day” was how Sigmund Engländer’s contemporaries described him. He was equally well known as a scoundrel and a womaniser.

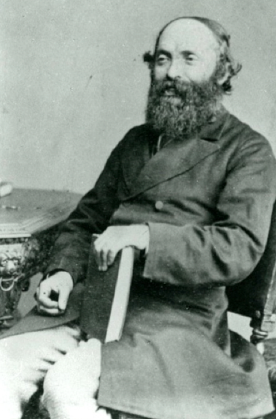

Outspoken and unconventional with views far to the left of Karl Marx, Engländer, pictured, forced Reuters to formalise one of the key tenets for the conduct of its journalists - impartiality. At the same time, straight-laced Victorian society looked askance at his numerous mistresses whom he continued to flaunt until well into old age.

Yet in the company’s early days, despite the storminess of their partnership, Julius Reuter owed a great deal to the man whose journalistic flair proved the perfect complement to his own business acumen. Indeed, Engländer often insisted that he had been co-founder of Reuters.

The two first met in Paris in 1849 when they both worked for Havas, the French news agency. Engländer had come to prominence the previous year during the Vienna revolution when, as a left-wing journalist, he had fought on the barricades. Born into a middle-class Jewish family in Moravia (now part of the Czech Republic) in 1823, his politics were an obvious reaction against a comfortable upbringing.

Order was restored in Vienna and Engländer was sentenced to death by the military. He escaped to Paris. Once there he resumed his political activities, mixing with revolutionaries such as Marx (who disliked him) and with literary figures such as Heinrich Heine. There is no evidence that his political views were shared by the much more conventional Reuter.

In France, Engländer’s revolutionary activities inevitably landed him in trouble once again. He was thrown into Mazas prison in Paris and subsequently deported. He chose to go to England because “I had never seen England and it was the land of the free”.

despite the storminess of their partnership, Julius Reuter owed a great deal to the man whose journalistic flair proved the perfect complement to his own business acumen

Reuter had settled in London in 1851. Within a few years Engländer was working for him (Engländer would have said with him) as chief editor. Possessing keen political instincts, he combined rare access to European political circles with an ability to spot a good story. He knew Emperor Napoleon III’s private secretary. Italian statesman Francesco Crispi was a personal friend.

However, the problem was always respectability. Reuter craved it; Engländer didn’t give a fig about it. He just about agreed to marry his wife because the (by then) Baroness de Reuter refused to have him in the house unless he did so. The marriage did not last.

Matters came to a head in 1871 when Engländer’s name appeared in the press in connection with a new political movement. He was called before a horrified Reuters board.

“The Chairman, having explained to him the necessity that all officials of the company should carefully abstain from all public connection with political associations of any kind whatever inasmuch as our character for impartiality on which we mainly depend for success would be seriously imperilled by any such suspicion of partisanship, Mr Engländer… pledged his word of honour to abstain from any connection with political movements…”

Engländer’s conduct had caused this principle to be enshrined as company policy. But in his case self-denial couldn’t last. Two years later, he published a book entitled The Abolition of the State.

Despite this fall from grace, Julius Reuter still recognised strengths in his old friend. He was immediately posted far away to Turkey to cover the long-running story of the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire and the rivalry of the great European powers for the spoils.

Characteristically, Reuter’s judgment proved right. The particular conditions of the region, requiring a subtle political understanding and resourcefulness in using secret codes and special agents to overcome censorship, brought out the best in Engländer. From his base in Constantinople he quickly established a reputation for getting news out of Turkey when rival news agencies failed.

He left Turkey in 1888 and travelled extensively throughout Europe on behalf of Reuters, ending his career as the company’s representative in Paris. He retired in 1894 at the age of 70 and was quickly and deliberately forgotten by the company. Julius, the first Baron, had long retired and the company was now represented by his son Herbert, the very upright and correct second Baron, and by his equally high Victorian chief editor, Frederick Dickinson. Engländer’s Bohemian disposition and life-style were unwelcome reminders of an era that had passed into history.

He died in Turin in 1902. Julius had died three years earlier. No one from Reuters went to the funeral; no cards were sent. ■

- « Previous

- Next »

- 30 of 49