Comment

The spy in Reuters' Saigon bureau

Sunday 4 September 2011

I am glad I do not have Nick Turner’s conscience. A nagging conscience that is forcing him, it seems, to agonise over a moral dilemma from the early years of the American war in Vietnam. A raw conscience that has been pricked by an article published recently in a New Zealand newspaper, compelling Nick to write a lengthy rebuttal.

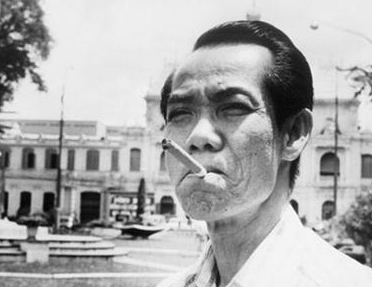

Nick’s dilemma is the stuff of a Graham Greene novel. Should he have denounced Pham Xuan An [photo], a distinguished Vietnamese journalist who worked with him in Saigon, as a Viet Cong agent? An was Reuters’ senior local reporter when Nick was bureau chief in South Vietnam in 1962-64. Later they were colleagues in the Saigon bureau of Time magazine. Nick says he was convinced from early on that An was working for the communists. He had no proof, though, so he did not alert his employers, either Reuters or Time Inc. Without the certainty of proof, he says, he could not justify denouncing An, which could have had dangerous or damaging consequences for him. And if An was in fact a VC agent, what about Nick’s own safety? An “would have had a variety of means at his disposal for ensuring that I met a sticky end,” Nick reflects. So he kept his own counsel.

After the war, An emerged as a senior communist agent, decorated by the government in Hanoi for his valuable intelligence work for the Viet Cong and North Vietnam. Western correspondents who had known An personally during the war were left to wonder whether they had suspected that he was a VC agent. Personally I didn’t; he was always extremely well informed, but he seemed too “westernised” to be a dedicated communist. Like other later Reuters bureau chiefs in Saigon, I was lucky not to have Nick’s moral dilemma: An no longer worked for Reuters so we did not have to worry about his reliability as a journalist or employee. He was just one of many sources around town.

Nick’s concern now is a newspaper report that he did in fact alert Time magazine about An - “but to no avail”. The report was published in New Zealand, his home country. It was written by a colleague who accompanied him on a recent trip to Vietnam. Nick is keen to set the record straight. The report was based on a “misunderstanding”. Nick is adamant that he did not, in his own word, “finger” An. He does not want anyone researching the subject on Google to believe he did.

But why is Nick so exercised by this ancient history? Is there more to it than meets the eye? Graham Greene would certainly have made a sub-plot of it, if not a whole novel.

Years after the American war, on a visit to Ho Chi Minh City in the 1990s, I invited An to lunch and asked him about his undercover mission for the communists. He said he had worked for them because he was a nationalist, a Vietnamese patriot, but strongly denied that he had ever been a communist. When I asked him to confirm that he had actually been a spy, whatever the cause, he hesitated and said he preferred to call himself “an analyst”. He said he just gave the Viet Cong his analysis and interpretation of events, like a journalist. “I never gave Reuters a wrong report,” he said. “I never gave any information that did any harm. I never put you or any of my colleagues in danger.”

- Nick Turner’s piece was written for Vietnam Old Hacks, a Google group for journalists who covered the war, following a recent visit to Vietnam by a group of old Asia hands from New Zealand. “Discussion inevitably arose during the visit about Pham Xuan An, who was for two and a half years my right-hand man and assistant journalist when I was Reuters bureau chief in Saigon in 1962-64, before he moved to the Time magazine bureau. Naturally there was curiosity among our travelling group about this man now famous as the ‘perfect spy’ and ‘the spy who loved us’.”

Turner said he suspected very strongly - “in fact I had no doubt whatever” - that An’s underlying sympathies were largely with the VC, although he clearly had issues with the policies, doctrines and methodologies of the NLF and their masters in Hanoi, and he could not have been a committed communist in the ideological sense. “I also guessed, correctly as it later turned out, that his unexplained absences from the Reuters office from time to time were to perform some mission for the VC. The question I am often asked is, did I warn people, including my colleagues in the media contingent in Saigon and in particular the staff of Time magazine, about my suspicions? ... the answer is No.

“During the time he was with Reuters, I found his analysis of events and of NLF-Hanoi policy very even-handed and reliable, and it included valuable critical assessment of the political, military and strategic problems faced by the communist side. He was the best in Saigon, and invaluable to Time, as he had been to Reuters. So I am sceptical about the assertions by some that An’s role included misleading the foreign media.”

Pham Xuan An died in 2006 aged 79. - Editor

- Stephen Somerville’s Analysis of a Spy is part of Frontlines: snapshots of history published by Reuters in 2001.

- « Previous

- Next »

- 1529 of 1808