Archives

Reuters and the False Armistice of 7 November 1918

Thursday 6 April 2017

During Thursday 7 November 1918, news spread around France that Germany had signed an armistice with the Allies and agreed to stop fighting - news, in other words, that the war had effectively ended that day.

Initially, it was confined to French and American military circles in Paris, but it was forwarded to military bases around France and eventually leaked to the general public. The Paris newspapers soon picked it up. Claiming, with reason, that the American Embassy had officially released the news, editors pressed their censors for permission to announce it in the afternoon issues. Dismissing the editors’ appeals, the censors categorically denied the peace news and prohibited any reference to it. They also instructed regional censors to quash it if it appeared in their areas. The French papers complied and took no direct part in spreading the news around the country. On 7 November, what they reported was the departure of a German armistice delegation for the Western Front - news the German government had released the previous day and which was now permitted for general release in France.

In New York City, not long before midday and five hours behind French time, the United Press agency’s office received a cablegram from the port of Brest on the Brittany coast of France. Roy Howard, the president of United Press, had sent it from there shortly before 4:30 pm French time. Its notorious message stated that Germany had signed an armistice at eleven o’clock that morning, that hostilities had ceased at two o’clock that afternoon, and American forces had taken the town of Sedan earlier in the day. It was all false news.

In New York City, not long before midday and five hours behind French time, the United Press agency’s office received a cablegram from the port of Brest on the Brittany coast of France. Roy Howard, the president of United Press, had sent it from there shortly before 4:30 pm French time. Its notorious message stated that Germany had signed an armistice at eleven o’clock that morning, that hostilities had ceased at two o’clock that afternoon, and American forces had taken the town of Sedan earlier in the day. It was all false news.

The cablegram took about six minutes to reach New York. By early afternoon, its message was racing around the United States to hundreds of newspapers subscribing to United Press services; by mid-afternoon, most American towns and cities had it. The same message travelled to Mexico, Cuba, Argentina and probably other Latin American countries. Crossing the northern border, it spread west through the Canadian Provinces. From Vancouver, it went to Australia and New Zealand, arriving during their morning of Friday 8 November. Similar false news started to spread around Britain shortly after 4:00 pm, just as it was starting to get dark. It seems to have arrived here directly from Paris. As there was no time difference between the two countries in November 1918, it must have left France some time before four o’clock that afternoon. News that the war was over, therefore, began circulating in Britain before Howard’s cablegram had left Brest for New York.

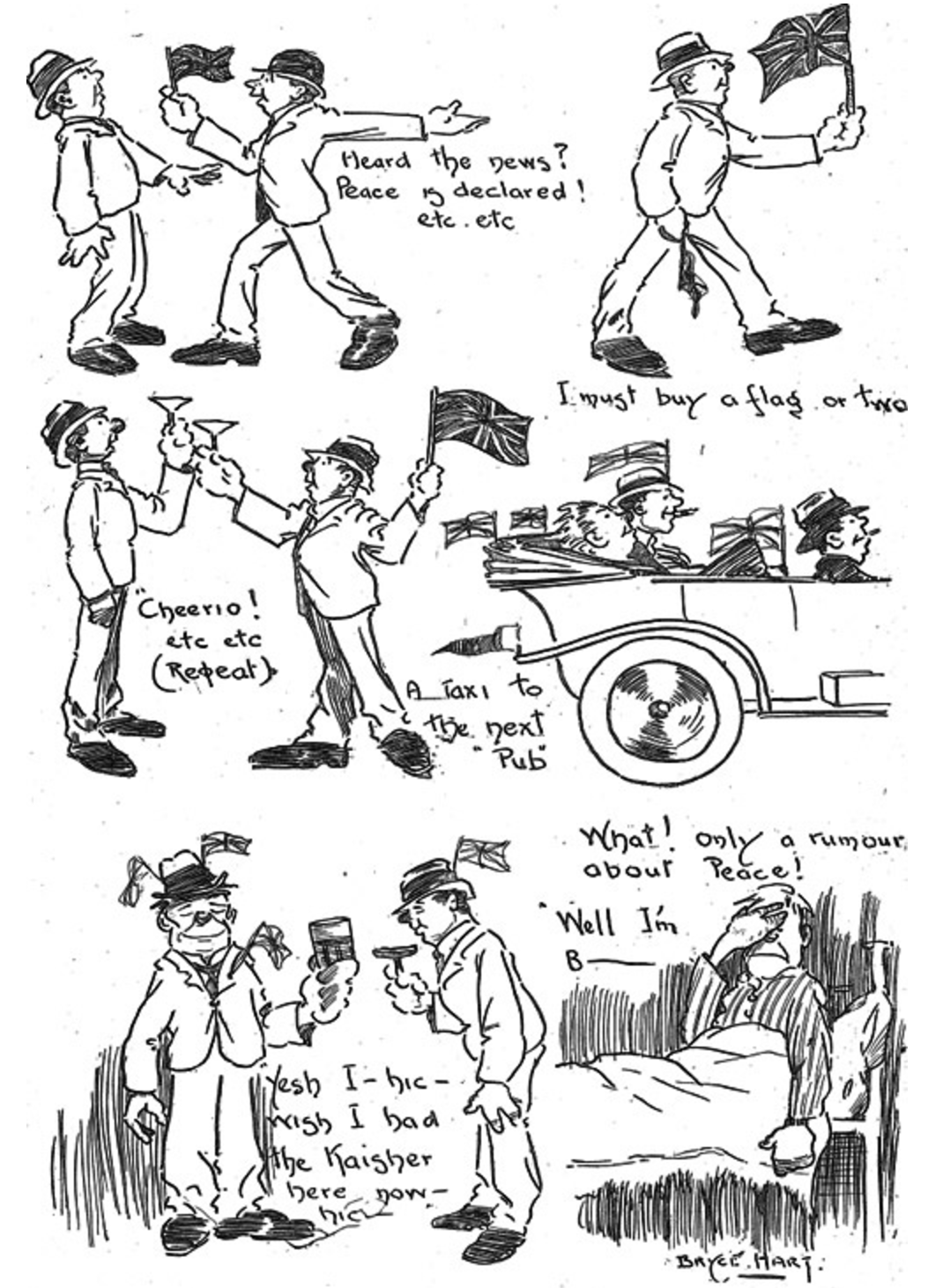

In France, Britain, the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand most people greeted the news with great joy. Ignoring Spanish flu precautions, they crowded into the streets and other public places to celebrate. They held patriotic parades, meetings and demonstrations. There were injuries, some fatal; at least one man in America was killed in a brawl over whether the news was true. Bonfires and mock trials of the Kaiser and his military staff, followed by hangings or burnings of their effigies, were popular features in Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Around Britain, people quickly filled streets kept dimly-lit by wartime regulations, but, under the regulations, could not fill the pubs until after 6:00 pm; in some parts, however, they defied regulations and rang church bells, set off fireworks and made loud noises by discharging an old cannon. In each country, in many places, and in spite of official refutations of the peace news, festivities continued well into the night. As one New Zealand newspaper explained it, people carried on celebrating “on general principles”.

All of this was part of the so-called False, or Premature, Armistice of 7 November 1918 - four days before the real Armistice that ended the Great War with a general cease-fire beginning at 11:00 am on Monday 11 November.

So, what had happened? How had the false news come about and then evaded the French censors to spread so extensively? What part did Reuters play in it all?

American Army Intelligence - known as G-2 - quickly investigated what had happened in Paris during Thursday 7th. They reported that the false news had arisen because a wireless message from German Supreme Command Headquarters in Spa (occupied Belgium) to Supreme Allied Commander Marshal Foch’s headquarters in Senlis (about 30 miles north of Paris) had been misinterpreted.

The message in question was one of a sequence, sent in clear Morse code, about the German armistice delegation then on its way from Berlin, via Spa, to meet Marshal Foch and receive the Allies’ armistice terms. It announced that German forces had been ordered to cease hostilities at 3:00 pm to enable the delegation to cross the front lines. German time was one hour ahead of French time, so for the Allies the declared German cease-fire was due to start at 2:00 pm their time.

The message did not make it clear that the afternoon cease-fire was to be purely local in its scope, limited to a French sector on the front lines where the armistice delegates were to cross. Senlis had sent instructions to Spa several hours earlier about where the delegates could cross, and made its own preparations for a local cease-fire there. According to the G-2 report, "some officers" (not named) had intercepted the message but misconstrued it, taking it to mean that a general cease-fire had been agreed and that the war, therefore, would end that afternoon.

As well as to US bases in France, the Liaison Service sent the misinformation to the American Embassy, which began releasing it to the public. The US Consul-General, for instance, announced it during a luncheon at the American Club, prompting newspaper editors to call the censors’ office for permission (refused) to print it. The US military attaché at the embassy, Major BH Warburton, cabled the news to Washington, DC, where it was successfully contained by the War and State Departments while they waited for separate verification from Paris. As they waited, however, Roy Howard’s message reached New York from Brest; it had spread around the country and beyond before they could officially deny it.

Roy Howard was in Brest on 7 November, having travelled overnight by train from Paris, to arrange his return to the United States. During the day, he had lunch with the US Army commander there, and in the afternoon met Admiral Henry Wilson, commander of US naval forces in France, at his headquarters in the town. When Howard was introduced, Admiral Wilson informed him that, just a few minutes previously, he had received a message from the naval attaché in Paris, Captain RH Jackson, that the armistice had been signed with Germany. The admiral had given the news to the townspeople whose cheering and singing, and a lively musical accompaniment from a US navy band in the town square, started to fill the streets.

Not surprisingly, Howard asked for a copy of the message and permission to send it to New York from the trans-Atlantic cable-head building not far from the naval headquarters. Wilson agreed and sent his interpreter along to help with the French officials. Banking on a time-lead from Brest over the peace-news messages he imagined other reporters were struggling to get out of Paris on congested wires, Howard hurried away with what he hoped would be the scoop of a lifetime.

When he and the interpreter, Ensign John Sellards, entered the telegraph building several minutes later, it was deserted except for the transmission room operators. Everyone else, including, crucially, the French censors, had readily accepted Admiral Wilson’s armistice news as official and were outside celebrating with the rest of the town. While Howard waited, Sellards took the armistice message straight to the transmission room and arranged for it to be sent to New York - without the censors seeing it first.

Afterwards, in America, Associated Press - major rivals - accused Howard and his organisation of perpetrating the “most flagrant and culpable act of public deception in the whole history of news gathering and dissemination” and called for appropriate penalties: at the least, Howard, an accredited war correspondent, to be court-martialled; United Press to pay for the cleaning up of New York City after the 7 November revelries. However, with a timely declaration of his own responsibility for issuing the Paris message as an official bulletin, Admiral Wilson exonerated them.

Reuters’ reputation - 'an agency which is recognised from its past record as the most reliable foreign news agency in the world' - was such that most accepted the armistice message without hesitation. The 'imprimatur of Reuter upon it' was verification enough

The armistice news reached Britain in a telegram to “the American Naval authorities in London”, according to a “strictly private & confidential” contemporary Reuter report. It was sent, presumably, from the American Embassy in Paris by military wire beyond the French censors’ authority. This is how Admiral Wilson was informed at his headquarters in Brest by naval attaché Captain Jackson, who may also have sent the telegram to his counterparts in London.

“An unofficial, but unimpeachable, channel” passed the information to Reuters, which lost little time in circulating it to Britain’s newspapers. The bulletin Reuters released, however, was not the same as the one Roy Howard sent to New York. A “literally correct” version of the message sent to London, it stated briefly that “according to official American information, the armistice with Germany was signed at 2.30.” Who at the agency authorised the news’ release is not certain; but it was most likely SC Clements, manager and secretary at the time, and author of the confidential report.

The armistice message reached some papers soon after 4:00 pm. Reuters’ reputation - “an agency which is recognised from its past record as the most reliable foreign news agency in the world” - was such that most accepted it without hesitation. The “imprimatur of Reuter upon it” was verification enough.

By 4:25 pm, however, a follow-on message from Reuters was circulating telling them, without any explanation, to cancel the armistice bulletin. Other newspapers received warnings from the Exchange Telegraph Company. These stated that the London Foreign Office, having received no information about the signing of an armistice with Germany, was advising newspapers that until “an authoritative statement” had been made, “no credence” should be given to the Reuter bulletin. Apparently, Reuters had received a similar caution, also from the Foreign Office, perhaps, which had rendered “the matter open to question”. Later in the evening, the Press Association, which had sent out the Reuter armistice bulletin to provincial newspapers, circulated other Foreign Office messages categorically denying the news.

In spite of the prompt warnings, a number of evening papers apparently released the false news within minutes of its receipt. Others withheld it, as advised. Where the news had already gone out, some acted swiftly to inform the public that it was not officially confirmed; but “in many parts of the country” the warnings failed “to catch up with the original story”. In any case, once released the news spread very quickly by word-of-mouth and telephone.

The next day, papers protested strongly about the false news, claiming it had caused great disappointment to people throughout the country; they questioned how it came to be “put on the wire” in the first place. The answer, they assumed, was “official ineptness”, of which the whole matter was a “glaring instance”. The “authorities” concerned deserved “the severest censure”.

The Official Press Bureau - the most likely of the “authorities” alluded to - came in for sharp criticism. Given its responsibility for vetting war news, the assumption was that the censors had failed to block the report, thereby inflicting a “great hoax” on the British public. A “blunder that ought not to be readily overlooked.” But the assumption was ill-founded: Reuters, it transpired, did not submit the message to the Press Bureau before sending it out.

By ignoring the Press Bureau and releasing the “official” American message, Reuters played a crucial rôle in events that led to the spread of the False Armistice in Britain - to the extent of ensuring that there would be a False Armistice here as well as in the other Allied countries. Indeed, it seems no exaggeration to state that SC Clements and Reuters were to the False Armistice in Britain what Roy Howard and United Press were to the False Armistice in the United States.

As well as disappointing the British public, the false armistice news brought about serious disruptions to the war effort. A number of papers reported that its sudden announcement emptied “scores of shops, factories, and works of all descriptions” as men and women stopped working to join in street celebrations or simply to go home. Night-shifts were affected as employees stayed at home. In South Wales, many collieries had to be closed for lack of miners (at a time of coal-shortages throughout Britain) and some furnaces were shut down. The overall result: several days would be needed before everything could be “resumed in full swing”.

As well as disappointing the British public, the false armistice news brought about serious disruptions to the war effort. A number of papers reported that its sudden announcement emptied “scores of shops, factories, and works of all descriptions” as men and women stopped working to join in street celebrations or simply to go home. Night-shifts were affected as employees stayed at home. In South Wales, many collieries had to be closed for lack of miners (at a time of coal-shortages throughout Britain) and some furnaces were shut down. The overall result: several days would be needed before everything could be “resumed in full swing”.

Reuters was deemed to be responsible for all of this. Not only had it circulated war news without submitting it to the censors, but the news turned out to be false, had caused workers to stop working and, as a consequence, production to be lost. In the opinion of the Attorney-General, “such large public mischief had… ensued”. The agency faced “drastic action” under the Defence of the Realm Act.

In the event, however, there were no court proceedings. Reuters’ good reputation and standing militated against a trial. As the Director of Public Prosecutions noted, “more than one Government department” interceded on behalf of Reuters “with a recital of [its] long, valuable and patriotic service [to the country]”; the Foreign Office in particular described the agency as having been of “inestimable usefulness”. Reuters received no more than an admonition.

Early in December, probably after the settlement, Clements sent his confidential report to newspaper editors. He wanted to assure them that Reuters had “acted in entire good faith” when it sent out the armistice message on 7 November, and to explain what had happened. He confessed that the agency had been “misled”. And divulged that it had received the news from the American naval authorities in London. News which turned out to be based on false information from Paris, emanating from “a person in the French Ministry of War”. The Americans, he intimated, “were in the same position”: they too had been misled.

By the time Clements’ letter was posted, the war had been over for almost four weeks. After 7 November, interest in the Allied countries quickly shifted from the false-armistice story to confirmed reports of the arrival of the German delegates, their meetings with Marshal Foch, and the prospect of a real armistice in the very near future. The False Armistice in Britain was undoubtedly soon forgotten, by the public and press alike. In the decades since, it has been largely overlooked and certainly under-reported as an aspect of Britain’s experience of the final days of the Great War.

In the United States, on the other hand, the False Armistice was newsworthy for many years. During the 1920s and 1930s, for instance, there were newspaper features and even an NBC programme about it. It gave rise to conspiracy theories of how the false news came about - theories Roy Howard himself endorsed. Nearly a century later, it is American sources containing references to it which internet searches usually find.

■

- « Previous

- Next »

- 47 of 49