Archives

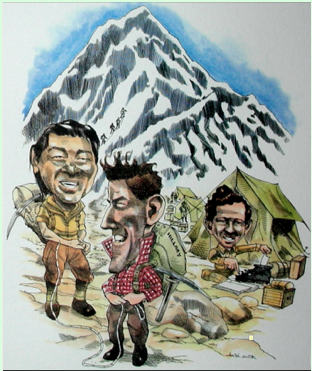

Everest conquered!

The scene is the breath-taking grandeur of Everest, the world’s highest mountain. A British climbing expedition will soon begin its victorious assault on the summit. Reuters has sent a correspondent. It is May 1953.

The scene is the breath-taking grandeur of Everest, the world’s highest mountain. A British climbing expedition will soon begin its victorious assault on the summit. Reuters has sent a correspondent. It is May 1953.

Peter Jackson, young and very fit, is now at nearly 5,500 metres (18,000 feet) on the Khumbu Glacier on his way to the expedition’s base camp.

Temporarily he has gone too high and is lost in a maze of ice pinnacles and crevasses at the foot of the great icefall leading to the Western Cym. One of his Sherpa porter/guides is suffering snow blindness from the intense glare off the ice and snow.

There are glacial torrents and treacherously thin ice but the party spots flags planted by the climbers to mark the way on the icefall. By following them down, sometimes cutting steps in the ice, Jackson finds the base camp hidden among the pinnacles.

Climbing Everest is not normally part of the day’s work for a Reuter correspondent but Jackson, based in Karachi, is a lover of mountains. A message from Sidney Mason, then Chief News Editor in Head Office, told him: “You assigned cover British Everest expedition. Get ready leave soonest...”

To leave “soonest” was not so easy as might be supposed. A visa for Nepal was hard to obtain and an expedition needs preparation. It was three weeks before Jackson was in Katmandu, capital of Nepal.

There he recruited 11 porters and an interpreter-aide and set off for Everest. Twelve-and-a-half days’ march took him to Namche Bazar, Sherpa village nearest to the mountain, and that was good going along a route crossing high passes, deep, hot valleys and forests of rhododendrons and pines.

It was a further three day climb to the base camp with four Sherpa porters accustomed to high altitudes.

Despite all this effort, prospects for a journalist were daunting because the climbing expedition had made a contract with The Times, of London, to give all its news to them. A Times man, in touch with the climbers by walkie-talkie radio, was the only occupant of the base camp and, though friendly, was resolutely uncommunicative.

Frustrating, but so be it! If the expedition succeeded, or failed, The Times could be its mouthpiece, but it would be Reuters that told the world. For the rest, Reuters had the only correspondent on the mountain independent of the expedition and would turn this to good effect: to what good effect was barely imagined when the Reuter Everest expedition was planned.

Reuters had the only correspondent on the mountain independent of the expedition and would turn this to good effect

Jackson made his headquarters in Thyangboche monastery, surely one of the most beautiful places on earth. Everest towered above it, with its summit visible over the Lhotse-Nuptse Ridge. It was within reach of Namche, and any messenger from Everest to Katmandu must pass that way.

Hospitable lamas provided a house for Reuters, and made a great pot of Tibetan tea whenever Jackson returned from a news-gathering trip. Some news, though scanty, filtered down from Everest and Jackson’s dispatches, reinforced by diligent support from Adrienne Farrell, correspondent in New Delhi, won wide success. It was Farrell who had first suggested his expedition, and who did much of the organisation.

Communications were by runner - usually a week to Katmandu for onward transmission to London. Occasionally a brief message could be passed over the official security radio from Namche Bazar.

When Everest was conquered, the British Expedition sent a runner to Namche to report their triumph in a coded radio message. It purported to announced that the advance camp had been abandoned because of bad snow conditions, and reached London late on 1 June, eve of Queen Elizabeth’s coronation.

Two days later the British climbers, freed from their contractual bond of silence, met Jackson at his monastery headquarters. Reuters had exclusive interviews with the Everest victors, Edmund Hillary and Sherpa ‘Tiger’ Tenzing Norgay, and with Colonel John Hunt, the expedition leader, that attracted world-wide newspaper and radio play.

As a reward for an exceptional reporting achievement one could hardly have asked for more, but more was to come. In Britain, home of the only rival to Reuters on the Everest story, The Times paid Reuters the tribute of devoting half a column to the interviews. The tally of British newspapers printing Jackson’s reports read like a directory of the national press.

It took Jackson 10 days to walk back to Katmandu, to find that the monsoon had stopped air services. So he walked over the mountains to India, having thus traversed Nepal on foot from North to South.

Next stop was New Delhi. There was much to talk over with Adrienne Farrell. They married the next year and now live in Switzerland, no longer with Reuters, but surrounded, naturally, by mountains.

■

- « Previous

- Next »

- 8 of 49