Archives

The Long view and the Nelson touch

Is there such a thing as a timely rather than an untimely death? In 1963 the word timely might have been used to describe the death of Walton “Tony” Cole, boss of Reuters.

Is there such a thing as a timely rather than an untimely death? In 1963 the word timely might have been used to describe the death of Walton “Tony” Cole, boss of Reuters.

His death from a heart attack at the age of only 50 cleared the way for the appointment of Gerald Long as his successor, aged 39. Long quickly became a pivotal figure in Reuters’ history.

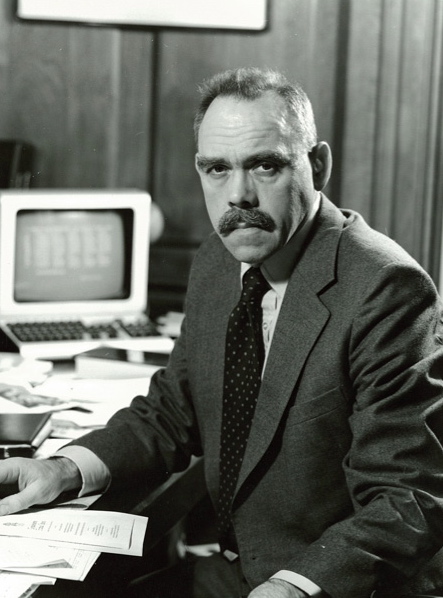

Tony Cole (photo), was a nice man. A Scotsman and a people person, he was loved for his herograms, short messages of congratulations which he liked to send to staff who had done particularly well or who had undertaken an editorial assignment with distinction. He was liked by everyone - or almost everyone. The only exceptions were those rare instances where he suspected that someone was growing a little too close to challenging him for his own job. But then Cole was always human and made no attempt to hide the fact. A man of ample proportions, he consumed in large quantities food which he was able to convert instantly into renewed energy. His capacity for hard work was unrivalled and - many privately feared - out of control.

Undoubtedly, Reuters was his life. But Cole’s Reuters was a traditional Reuters focused on its newsroom. Born in 1912, and honing his craft during the 30s and the Second World War, Tony Cole was - first, foremost, and through and through - a newsman.

In London’s Fleet Street, the afternoon of 25 January 1963 was cold, dark and foggy. On the seventh floor of the Reuters building, Cole had reached a delicate point in sensitive negotiations with Belga, the Belgian news agency. Belga’s chief was on his way to London by plane to continue discussions. Suffering from a heavy cold and feeling unwell, Cole decided to lie down for a rest on the sofa in his office. When his secretary came to tell him that it was almost time for his meeting, she discovered him dead from a massive heart attack.

The man chosen to succeed him could not have been more different.

Few would have described Gerald Long (photo), as a nice man. A people person he was not. Born in 1923, the son of a postman, he possessed an aggressive streak which could cross the line into bullying. He was grumpy, short-tempered, arrogant and intolerant of fools. Exceptionally intelligent, he joined Reuters as a graduate recruited from Cambridge University where he had read modern languages. He spoke French and German like a native. He adored French and German literature, music and art and - like his predecessor - he loved food and drink. However, unlike Cole, his interest centered on the cooking and preparation of food. A keen amateur chef, his passion was for quality rather than quantity. He could talk food at the drop of a hat, taking it to a level which, for many, seemed a boring obsession.

Few would have described Gerald Long (photo), as a nice man. A people person he was not. Born in 1923, the son of a postman, he possessed an aggressive streak which could cross the line into bullying. He was grumpy, short-tempered, arrogant and intolerant of fools. Exceptionally intelligent, he joined Reuters as a graduate recruited from Cambridge University where he had read modern languages. He spoke French and German like a native. He adored French and German literature, music and art and - like his predecessor - he loved food and drink. However, unlike Cole, his interest centered on the cooking and preparation of food. A keen amateur chef, his passion was for quality rather than quantity. He could talk food at the drop of a hat, taking it to a level which, for many, seemed a boring obsession.

In addition to an interest in food, Long shared two further characteristics with Tony Cole. He was free from vanity. He also steadfastly believed in Reuters and all that it stood for.

As the 1960s advanced, two men - both slightly younger than Long - were increasingly attracting notice.

Michael Nelson was a Londoner, born in 1929. Joining the company as a graduate trainee in 1952, he had been recruited, not to the more glamorous general news side, but to Comtelburo (Reuters Economic Services). By 1962 he had emerged as Comtelburo’s manager.

Over the next 20 years, Nelson oversaw the introduction of a succession of computerised and other products for the distribution of financial and economic information. Earning great profits, these products shifted the internal emphasis away from that of an old-style traditional news agency. For the first time, Reuters had become a highly profitable company. Nelson and his team did not at first create these products although on occasions they suggested improvements. Rather, Nelson personally evaluated every possibility, giving steady support to a few selected initiatives. He knew that it was vital to be both bold and cautious. Spare money was thin on the ground. An expensive mistake might spell the end of the company.

Another young man joined Comtelburo as a recruit in 1952. This was Glen Renfrew, an Australian, born in 1928. Like Nelson, Renfrew was aware of the exciting possibilities being opened up by the evolving new technology. He was convinced that only through introducing such technology could Reuters hope to protect its existing contracts, attract new business and improve its always precarious financial position. In 1964, he was invited by Long to be manager of Comtelburo’s newly-formed computer division.

How much of this technology did Long fully understand?

Long had no background in technology. His capacity to understand how the new systems worked was limited. But he was a realist. He had no illusions about the stark fact that if Reuters did not quickly adopt the latest technology, customers would turn to competitors who were already doing so. Moreover, he grasped that far more was at stake than simply offering greater speed. The revolution in data processing rendered possible the circulation of both general news and economic information to all customers simultaneously. Indeed, it would soon lead to the creation of entirely new products allowing customers to select and retrieve only the data that they themselves required. Instant ubiquity combined with personal choice - nothing would ever be the same again.

In July 1965 Long compared the positions of Reuters general news and Comtelburo services. “Reuters main function in its general news making services is to provide a service; Comtelburo’s chief aim is to make money.” Only a month earlier, he had reminded his senior managers that no other firm possessed such a good economic news network and such expertise. “We must make a great effort to ensure that everyone in the organisation realises how much we depend on these services”. Michael Nelson and Glen Renfrew had ensured that Comtelburo’s days as an unglamorous sister were gone for ever.

Reuters had changed both in outlook and in its perception of itself from that foggy January afternoon - a mere year and a half earlier. Yet this was only the beginning. Over the next 16 years of Gerry Long’s reign, the company would go on to launch Stockmaster, Videomaster and (in 1973) most historically important of all, Monitor. In 1981, when he decided to step down, Reuters had been transformed from the time of Tony Cole.

What if Cole had survived his heart attack and remained at the head of Reuters for a further 10 years? Would the same major changes have taken place? Would Cole - essentially a pre-Second World War newsman - have had the vision to preside over such a fundamental reinvention of the company? At his death his commitment to Reuters was total. But was he still marking old-fashioned time? Would change have still come to Reuters, albeit at a slower pace? Or would the company have continued its undoubted decline as a venerable news agency, struggling to find a role in a radically changing world?

History is full of such unanswerable questions. ■

- « Previous

- Next »

- 11 of 49