Archives

The Baron's management philosophy

Paul Julius Reuter was quite a good businessman. True, his earlier career had thrown up more failures than successes. But he had shown sufficient shrewdness to learn from his mistakes. After 1851 when he established his fledgling business in London there was still the occasional failure. Gradually however these failures became fewer.

Paul Julius Reuter was quite a good businessman. True, his earlier career had thrown up more failures than successes. But he had shown sufficient shrewdness to learn from his mistakes. After 1851 when he established his fledgling business in London there was still the occasional failure. Gradually however these failures became fewer.

What other factors contributed to his ultimate success?

In earlier blog entries, I highlighted Reuter’s tremendous luck in finding exactly the right wife at the right time. Clementine Magnus was intelligent, well-educated, ambitious and energetic. Unusually for the 1840s and 50s, she was prepared to work “hands-on” with her husband, getting their new venture off the ground. She knew as much about the telegraphic news business as he did. The marriage was a long and happy one. Were it not for this drive, unswerving support and total belief in him, Julius Reuter might well have ended up as no more than a footnote in history.

The founder of Reuters not only found the right wife, he found the right staff for his Victorian agency. Indeed, he was a very good judge of people. In this, he tended towards the long view - as in the notable case of Sigmund Engländer, his very first editor.

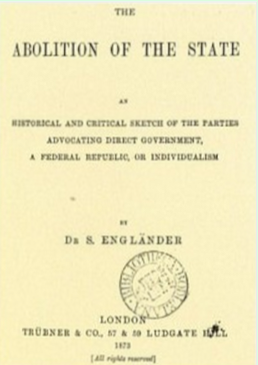

Engländer made no secret of holding political views somewhat to the left of Karl Marx, with whom he did not get on. As if this was not awkward enough for his boss, in 1873 he published a book entitled The Abolition of the State.

For most 19th century businessmen, such a flagrant overstepping of the capitalist mark would have been the last straw. But even at this point Reuter was prepared to recognise that Engländer had skills from which he - and by extension, Reuters - could still benefit. So he didn’t sack him. Instead, he posted him to far-off Turkey. Once there, his mission was to cover the long-running story of the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire and the competition between the great European powers for the spoils.

Characteristically, Reuter’s judgment proved to be right. The peculiar conditions of the region, requiring subtle political understanding and resourcefulness in using secret codes and special agents to overcome censorship were just up Engländer’s street. Based in Constantinople, he quickly ensured that Reuters gained an enviable reputation for getting news out of Turkey when rival news agencies could not.

A later Reuters editor was George Douglas Williams. He went on to have a long career with the company, remaining in post for a remarkable 24 years. However, as a young sub-editor, Williams was another whose career could have ended virtually before it began, but for Reuter’s perception and judgment.

Williams had joined Reuters in 1860 when the night office was located at King Street, London. The office backed directly onto the garden and back yard of Julius Reuter’s own house in Finsbury Square. Foreign news was not yet continuous. During the long intervals when no news was to hand and there was virtually nothing to do, night staff were permitted to doze. And so it was that Williams was asleep when news of the first big battle of the American Civil War at Bull Run arrived by telegram. Try as he might, the young telegraph boy failed to rouse him from his slumbers. At last he had no choice but to leave the message on Williams’s chest. Meanwhile, Williams slept on, untroubled until “in the grey light of dawn he was aroused by the spectacle of his employer in his dressing gown and slippers standing over his bed and shaking the fateful message in his face.” As was his custom, Reuter had come across the garden to see what news had arrived overnight.

Such a lapse could well have cost Williams his job. But once again Reuter took the unexpected decision to overlook what had happened. Reuters, he estimated, would still be better off with Williams rather than without him.

Here was yet another case of Julius Reuter’s intuitive capacity to recognise that, even after the most serious of lapses, there may still be a case for giving anyone a second chance.

Has this management philosophy survived into the 21st century? I, of course, could not possibly comment. ■

- « Previous

- Next »

- 36 of 49