On Christmas Day, Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe ate roast chicken in prison and made a Christmas pudding, explaining to her fellow prisoners that it is normally covered in brandy and set alight. Her three-year-old daughter, Gabriella, was invited to the home of the British ambassador to Iran, where she was given a colouring book.

Richard Ratcliffe spent the day without his wife and daughter, and marked the occasion in restrained fashion. He said he would not buy a Christmas tree, because he had promised he would not do so until they could all decorate it together.

There had been a brief moment of optimism that Nazanin, who has been in Iran’s notorious Evin prison since early 2016, might be released in time to decorate the tree this year.But she is still in Tehran, where she is serving a five-year sentence over what her family has always insisted are ludicrous accusations. Gabriella is stuck in Iran, estranged from her father, because the authorities there confiscated her passport.

In the run-up to Christmas Day, the only decoration in the family’s home was an untouched advent calendar intended for Gabriella.

Richard prefers to think of it as postponing Christmas this year; the family’s second one apart. He even carried out his family tradition of adding another Christmas decoration to their collection this year – as much as a way of willing his wife’s release as anything else.

But he will not touch the box until his wife and child are home. “I promised her we’d buy the tree. So, in my head, that’s when you decorate,” he says, sitting in the family’s flat a few days before Christmas.

Events in recent weeks first led the family to fear Nazanin’s nightmare could be extended by another five years, then to hope that it might end at any moment.

The dual British-Iranian national was detained in Tehran’s Imam Khomeini airport in April 2016 as she sought to return from a holiday in the country of her birth. She had been visiting her parents with her young daughter but the Iranian authorities accused her of plotting to topple the regime.

She was sentenced to five years in prison and her family hoped she would soon be eligible for early release. But she was put in further jeopardy by comments made by the British foreign secretary, Boris Johnson, the person ultimately responsible for the diplomatic effort to free her.

Johnson wrongly told parliament that Nazanin was teaching journalists in Iran. That was quickly seized upon by authorities in Tehran, who sought to use the foreign secretary’s slip to imprison her for a further five years. She was, in fact, just a mother on holiday, Johnson eventually publicly made clear. And, following his subsequent trip to Iran in early December, there were hopes a breakthrough could be made.

Richard does not hold the UK government responsible for his wife’s incarceration but he is critical of the length of time it took to “criticise her detention - how long it took for us to meet the foreign secretary”.

That meeting came only after Johnson’s professional fate became entwined with Nazanin’s case late this year.

Even when the family is finally reunited, Richard recognises it will be a long time before it is fully reconciled. He will need to rebuild his relationships with both his wife and his daughter, who has spent so much of her formative years separated from him – living with her grandparents in Iran – that he says they no longer truly share a language.

“What daddy means to her now is quite different from what daddy meant 18 months ago. Now I’m a bloke at the end of the phone who might be interesting and might not be, depending on what else is happening. I’m always a poor second to a good cartoon.

“She’s young enough not to understand too much, not to worry about too much, so I’m still sure we can pick it up again but it’ll take time and, obviously, she’s learned to rely on those around her.”

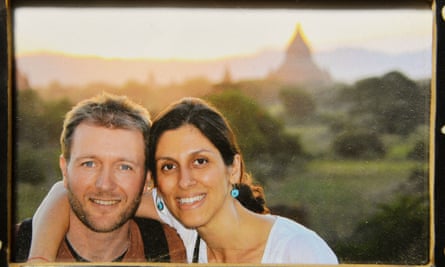

The home to which he hopes Nazanin and Gabriella will soon return bears some marks of what it was when they were last there as a family. There are pictures of the couple together on the walls, as well as a child’s paintings on the fridge and children’s toys all packed neatly away.

But Richard admits he is not emotionally prepared for his family’s return to the UK, whenever that happens. There will be “new bridges to cross”, he says.

“If you spend 20 months apart from your partner, it takes time to rebuild on the basic levels, let alone the fact that there’s a profound gap between what she’s been through and what I’ve been through.

“I can be sympathetic, I can be empathetic. But the chances of me ever really understanding what [Nazanin has] been through, if she sits with someone who’s also been in that prison, they’ll have an innate understanding of each other’s experience that I couldn’t possibly have. So, that will always be a gap.”

Then there is his own mental and emotional state. “I typically don’t want to show feeling sad. I’ve had my moments. I feel it creeps up on you, though. Sometimes, it can all just be a bit harder.

“There is the bit where it gets quiet enough and your feelings catch up. There’ll be an odd day when I plan to do stuff and the day just disappears kind of lying on the sofa, feeling sad and glum.”

Still, he says, there are parts of the past two years that will have strengthened the couple. They have been “profoundly stress-tested”, Richard says. Such thoughts are, in one sense, optimistic – there may be some way yet to go. With Nazanin’s status so uncertain, Richard is reluctant even to allow himself to seriously envisage the possibility that his family could be reunited one day soon. He is quite prepared for the possibility that January finds him renewing his campaign.

He has been here before – last year – and he knows that allowing a plan for Christmas, New Year and his wife’s birthday to crystallise in his mind, not to mention buying a tree, means the disappointment will only be greater if his family cannot be there.