People

Notes on the art of being apart

Tuesday 28 April 2015

How do you keep romance alive in a relationship where work demands frequently separate you and your partner?

How do you keep romance alive in a relationship where work demands frequently separate you and your partner?

Reuters editor-in-chief Stephen Adler and his wife, novelist Lisa Grunwald (photo) - 27 years married - know the secret and are sharing it.

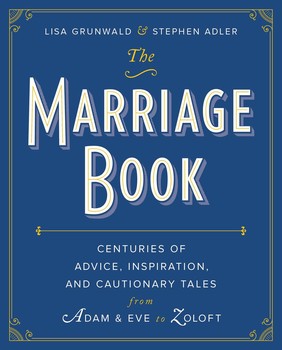

It's in a book they’ve co-authored: The Marriage Book: Centuries of Advice, Inspiration and Cautionary Tales, from Adam & Eve to Zoloft, to be published by Simon & Schuster in May.

Grunwald, writing in The New York Times, confides: “I always slip a card into his briefcase when he flies somewhere. Sometimes I add an old picture or a heart-shaped piece of coral. I do this, in part, so that if his plane crashes, I’ll know I’ve said a last I-love-you.

“So far, this strategy seems to have kept his planes aloft. But, really, these notes are like bookmarks in the story of our marriage, each one created to hold a place until we’re together again.”

Grunwald recalls she accompanied her husband on his first business trip - to Toronto - “and I brought back a hotel shower cap. But I thought: Yes, this is marriage. You do whatever you can so that you’ll wake up in the same bed.”

It didn’t last. His work commitments, her own writing job and the demands of two children meant that “Unable to go on work jaunts together, we did what we thought was the next best thing: We tried to talk on the phone every day. This was before the cellphone, so we sometimes failed to connect at all. When we did, though, we aimed for full debriefings: all the meetings and meals, the gossip and grind, of our days apart.”

Grunwald writes of other spousal separations in other ages - John and Abigail Adams, for example, Dylan Thomas and his Irish wife, Caitlin, Pliny the Younger and Calpurnia, and she notes that their communication depended on husbands and wives understanding that apart was truly apart, that they had no life together except their lives in the past and future.

“Stephen and I were trying to be together while being apart, and instead of a florid Welsh poet, I got a harried New York journalist. Instead of a sweet Irish heart, he got a disconcerted writer facing work and children and the unexpected realization that the quaint wifely role had definitely lost the quaint.

“Stephen and I were trying to be together while being apart, and instead of a florid Welsh poet, I got a harried New York journalist. Instead of a sweet Irish heart, he got a disconcerted writer facing work and children and the unexpected realization that the quaint wifely role had definitely lost the quaint.

“Absence was making the heart grow cranky. When we talked, I imagined him in his hotel room, rolling his eyes and mouthing the words ‘two minutes’ to some colleague waiting to hit the town.”

Grunwald says she missed her husband, “but it was better to want him than to need him. The haunting mystery of any marriage - ‘What would I do without you?’ - is often a rhetorical endearment…

“After more than two decades of marriage, we had finally gotten it down. We would talk when we could and keep it brief. If something big arose, we would share it. But mainly, we said what people in love say. The freedom from all the details allowed us to miss each other, and coming together again suddenly provided a fluttery joy.

“Good thing we had found all this wisdom, because it came just before my doctor told me, seven years ago now, that I had multiple sclerosis. My energy, even for simple tasks, became finite. Daily, my batteries drained. My balance was off. I broke an arm.”

“Stephen was now head of a global news agency with offices all over the world, and yet he was traveling less than he had in a decade. The first year or two after I got sick, he kept his travel stateside. But it was clear he would have to go much farther to spend real time with colleagues abroad.”

When he left on a trip to China in February 2011, “We kissed goodbye and flashed reassuring smiles that were filled with equal amounts of love and lying. But no trip had ever felt more essential. He needed a break from the me who was sick, and I needed a break from the guy who needed a break from the me who was sick.

“Friends reminded him how easy it would be to stay in touch. There were iPhones. Wi-Fi everywhere. Skype. We could text and email at any hour. But we had learned our lesson, back when illness had nothing to do with it: For us, apart, if we did it right, allowed us to be our better selves, to rise above the daily dreck and feel the kind of marital bond that’s sometimes strongest when it’s stretched…

“I stayed home, and Stephen went to Asia. We talked occasionally, but we didn’t Skype or text. He had left a letter on my night table - not Pliny or Dylan Thomas, perhaps, but pretty majestic in its own right. And I had put a note in his bag.” ■

- « Previous

- Next »

- 271 of 515