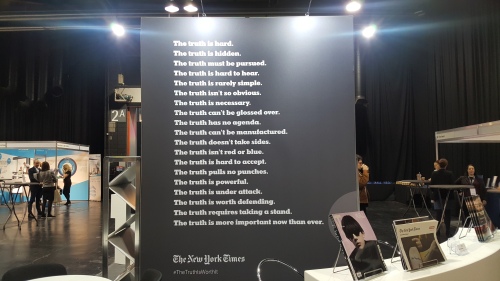

“The truth is hard”

I’ve come across this quote repeatedly in the past year, most frequently in the form of ads for the New York Times at various media events. It always makes me think of the divide between the vanguard and the rearguard over the future of journalism.

New York Times ad at the World News Media Congress in Glasgow, June 2019

One truth that is not hard is this: in my first year as Director of the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, I have been truly and thoroughly inspired by the ambition, desire, and fight for change in journalism among many journalists, editors, and media leaders.

Let’s call them the vanguard.

While the vanguard is often young, it is not only young – Maria Ressa at Rappler and Marty Baron of the Washington Post are not spring chickens, and they are forging towards the future of journalism, as are Kath Viner at the Guardian, Siddharth Varadarajan from The Wire, and many others who have been through a thing or two. But perhaps it is also about age—the absolutely certainty among many that journalism as we knew it will not thrive in the 21st century, combined with suspicion among some older journalists that it may yet last their time out.

That latter part is a harder truth to face, the persistence of a mindset that risks doing lasting damage to the profession of journalism and the news media organizations that enable it, and make a number of already tough challenges even tougher. It is the mindset of those who say they believe that people will cool on their smartphones and pick up print, that people will ditch video-on-demand and return to linear scheduled broadcasting, that journalists can safely condescend upon and harmlessly ridicule as conspicuously woke or ridiculously politically correct the values and priorities of new generations.

This is the rearguard.

This mindset is invisible at most “future of journalism” gatherings, but I meet at least some of them at every industry event I attend, many in most media organization I visit, and they have plenty of kindred spirits among (older) policymakers.

The rearguard thinks the problem is that the world has changed too much. The vanguard thinks the problem is that journalism hasn’t changed enough.

Nothing is ever black or white, but crudely put, I see one group of journalists and media leaders who want to develop and change the profession and the funding models that sustain it so they are fit for a changing world and a digital media environment. But I also, constantly, everywhere, come across another group of journalists and media leaders who do not see it this way, who would rather pour their energy into vain attempts at trying to restore a romanticized past, airbrushed of its shortcomings, idealized for its (very real) virtues, and valued for the stability it offered many, both in terms of professional security and career advancement as well as in terms of the media business.

From my experience, the younger generation is overwhelmingly in the first group. The older generation? More mixed. The vanguard is full of women and more diverse. The rearguard full of white men like me.

Both the vanguard and the rearguard care about journalism, but the divide between them is a problem for the profession and the industry, for while the first group is fighting for various visions of an uncertain future, the second group is defending a defunct past that—while it had much to offer—will in many ways no longer serve. The older parts of the rearguard won’t even necessarily experience the full consequences of their own conservatism. Business as usual, perhaps with a bit of hand-waving about AI and blockchain for garnish, may in fact last their time out (if they are close enough to retirement). But in the process, this mindset will continue to undermine journalism’s ability to adapt, remake, and renew itself, and the profession as a whole, especially younger journalists, will have to live with the consequences of this conservatism. This is an often unacknowledged, but ever-present and very real, generational divide in journalism.

“The truth isn’t so obvious”

That’s another part of that same New York Times advertisement. And don’t we know it. When we redefined the Reuters Institute’s mission this year as “exploring the future of journalism worldwide through debate, engagement, and research”, it was premised on three things: (1) we don’t want to fight yesterday’s battles, but will look toward the future, (2) we don’t know what that future looks like, or should look like, so we want to explore it by all means available, and (3) we don’t believe anyone can succeed on this journey on their own, so we will focus on collaboration and conversation.

But there are some things we do know, and while these things may count among the truths that the New York Times counts as hard to hear, they are also truths that cannot be glossed over.

- Journalism is important for democracy. (Yes – often for good, but sometimes for ill.)

- Journalism is important for holding communities and societies together. (Yes – but also sometimes dividing them.)

- Journalism is an important part of the media and technology business. (Yes – but small and shrinking.)

In my experience, many in the rearguard would like to stop with just the celebratory first part of each statement. They seem to prefer an after-dinner speech celebrating the value of journalism at its best to an accurate description of journalism and its actual state.

But, as each of the parentheses suggest, we cannot truthfully stop there.

And while an after-dinner speech may feel good, planning your future as if it is an analysis will lead to catastrophic, avoidable outcomes.

Furthermore, while the public may be willing to at least consider the after-dinner speech version of what journalism is and what it means (we still have a reservoir of goodwill), they don’t buy it as a description.

Much of the public does not trust journalism, consider it to be of limited value (or even a drain on them), and pay little attention to it. This disregard goes well beyond the imperfections that most journalists are already willing to contemplate.

Consider just three findings from Reuters Institute research in the past year as an illustration of each point—

- Trust: Since 2015, we have seen a drop of trust in news by about ten percentage points in many of the countries we have been tracking in the Digital News Report, and by now less than half of our respondents say they trust most news most of the time.

- Value: When asked in 2019 whether the news media help them understand the news of the day, just 51 percent agreed. (Fifty-one percent! Nearly half the public does not find that news media help them understand the news.) And a third say they actively try to avoid news often or sometimes.

- Attention: Online, people spend only about three percent of their time with news and information. A major public service media organization like the BBC still accounts for 63 percent of linear radio listening in the UK and 31 percent of linear television viewing, but just 1.5 percent of digital media use (and BBC News just 0.6%). Online news reach is a mile wide but all too often only a quarter-inch deep—and increasingly unequally distributed.

I cannot stress enough how important it is that we face these issues. Lucy Küng has a passage from an interview that she often returns to in discussions of the business of news.

Interviewer: “What was your biggest mistake?”

Media industry CEO: “I always say that if I could go back ten years, … , I would not be saying, ‘The Internet’s going to be big’ … what I would really be saying is, ‘Your business is going to be more screwed than you can even conceive of now. Your worst case scenario is just a scratch’.”

“Just a scratch.” What if this applies to journalism’s connection to the public as well as to the business of news?

Journalism exists in the context of its audience. Its public value, its political power, its social significance, its viability as a business, its legitimacy as a beneficiary of public and philanthropic funding—all of it is premised on its connection with its audience. That connection is in many cases hanging by a thread, and it is on us to retain, renew, and reinforce it.

The vanguard understands this. The rearguard refuses to accept it.

“The truth is powerful”

The push-back that we often get when we present findings like these suggests that some in the profession and the industry prefer tame cheerleaders to independent researchers, and dismiss challenging findings as depressing doom-mongering. Some, it seems, would prefer only research that suggests journalism is great, and was even greater in the past.

Most of the vanguard, in contrast, embrace our research, as much of it again and again underlines the absolute necessity of change, change that will have to go well beyond this or that question of tactics, optimization, or refinement, and concerns basic question of purpose (what are we for?), value (what problems are we trying to solve for whom?), and strategy (how do we get to where we need to be to do that?).

The rearguard? The prevailing assumption there seems to be that hard truths are for other people.

The attitude seems to be that we should romanticize the journalism that, for all its values, also arguably failed us on climate change, in the run-up to the financial crisis, and in uncritical coverage of digital media throughout the 2000s, a journalism that has often seemed as out of touch with the energies behind #BlackLivesMatter, #Fightfor15, #MeToo as with the groundswells of support for Brexit, Narendra Modi, and Donald Trump, a journalism that is still all too often based on a mass media business model that won’t make sense much longer.

But hard truths aren’t only for other people. They are also for us.

At the Reuters Institute, we will continue to pursue independent, evidence-based, internationally-oriented research on as many of the major issues facing journalism worldwide as we can, whether the findings are comforting or not, whether they concern the many external challenges over which we have little control (political pressure, increasingly challenging business, the growth of platform companies), or the internal ones that we, together, can in fact address (how we engage with people, create value and gain trust, and change our own organizations).

The Reuters Institute is not on anybody’s side, vanguard or rearguard, but our findings are overwhelmingly aligned with the vanguard’s view of the world, and rarely the rearguard’s. (If the facts change, our views will too.) We will explore the future of journalism with anyone who wants to engage (and with the help of a new Steering Committee and a new Advisory Board that better reflect the diversity of our journalism fellowship program and the wider profession).

We hope we—through debate, engagement, and research—can help more journalists, editors, and media leaders develop their own understanding of (a) how our media environment is changing, (b) what it means for their organization, and (c) what they can do to succeed professionally and organizationally in that changing environment.

Everyone should make up their own mind, but with every program we run, every event we attend, every report we publish, I see a few more people – some young, some old – come to the conclusion that more of the same isn’t the answer, that going back to the past is neither right nor possible, and that we have to forge ahead towards an uncertain future instead. In short I see them joining the vanguard, a vanguard where there’s always room for more, and a vanguard that needs experience as much as it needs energy, insight as much as it needs innovation.

That matters, because rearguard action won’t lead us to the future, and no one else is riding to the rescue – not platforms, not foundations, and not governments. If journalism and the business of news that sustains (and constrains) it is to be saved, it has to save itself, if it is to be remade, it has to remake itself.

And I promise you this: we will continue to call it as we see it, despite the stream of angry emails I get every time our research falls short of the rearguard’s self-understanding, or challenge some of the truisms of how journalism and the news industry like to present itself to the public and to policymakers.

We do this just as journalism seek truth and report it, not because it knows exactly what the future will hold, or precisely how to solve the issues of our day, but because journalism, at its best, is premised on the belief that the truth is powerful. That people with access to relevant reliable information and a chance to discuss it with their peers will make better choices.

That same role is the one that we to the best of our ability try to play vis-à-vis the profession, the news media industry, and its various interlocutors – provide independent evidence and analysis, foster and host debate, insistent on the importance of facing the big issues, however inconvenient and uncomfortable it might be for various incumbents and elites. This, a focus on exploring the future of journalism through debate, engagement, and research, is our answer to the question I asked last year when I took the role as Director: what we can do to help journalists (and all of us who rely on journalism) reinvent the profession and the industry?

We don’t know what the answers are, and we don’t know what exactly the future holds for journalism, but we want to be part of that journey, and we will continue the search for answers through our journalism fellowship programs, our leadership programs, and our research programs.

Not as tame cheerleaders (or depressed doom-mongers). But as explorers of the future of journalism.

We hope you’ll join us.