Facebook’s latest content blunder involves a Norwegian newspaper and an iconic photograph. It is the perfect example of the social network’s inability to deal with its responsibilities as a dominant news distributor.

It’s all about the terrible 1967 picture of a naked nine-year old girl, severely burned, fleeing a napalm bombing in Vietnam. The photographer, Nick Ut, won a Pulitzer prize.

There is no doubt that this image was a factor in ending the Vietnam war.

Nor is there any doubt that Facebook’s initial decision to remove the picture illustrates how far the social network is from exhibiting the discernment required to properly handle the immense flow of information it carries.

Here is the background, as told by Espen Egil Hansen, Norwegian newspaper Aftenposten’s editor-in-chief, in an open letter to Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg.

A few weeks ago, Norwegian author Tom Egeland posted an entry on Facebook about, and including, seven photographs that changed the history of warfare. You in turn removed the picture of a naked Kim Phuc, fleeing from the napalm bombs—one of the world’s most famous war photographs.

Tom then rendered Kim Phuc’s criticism against Facebook for banning her picture. Facebook reacted by excluding Tom and prevented him from posting a new entry.

Listen, Mark, this is serious. First you create rules that don’t distinguish between child pornography and famous war photographs. Then you practice these rules without allowing space for good judgement. Finally you even censor criticism against and a discussion about the decision—and you punish the person who dares to voice criticism.

I happen to know Espen Egil Hansen. We met many years ago when I worked for the Norwegian media group Schibsted ASA (my Monday Notes actually started there, as an internal newsletter for Schibsted’s management). For me, Espen is the embodiment of a new generation of great editors: bold, fiercely independent, rigorous, tech savvy, and supported by a news organization that doesn’t trifle with journalism ethics. This explains the impact of its public stance against Facebook’s content censorship.

After a two-day gale-force manure storm, Facebook reversed its decision and reposted the picture. (Espen’s page also carries rare footage of Kim Phuc’s tragedy; on that matter, our French-speaking readers can read this remarkable 2012 piece by Annick Cojean in Le Monde; it tells the story of the picture and the whereabouts of its actors 45 years later).

That Facebook finally made the right decision (and explained it) doesn’t really make the problem go away:

- Facebook has indeed become one of the most powerful editors on the planet.

- The company’s ways make it a dangerously incompetent editor that compromises the diversity of information—sources, genres, styles, topics.

- If left unattended, the combination of these two factors can’t but negatively impact the quality of information on a media site now serving 1.7 billion people.

Let’s take a closer look.

On the first point, at multiple occasions, I have stated my views of Facebook’s domination of the news distribution system.

In short, a growing percentage of the population get its news from Facebook. This negatively impacts the news industry in two ways.

One, it dilutes existing brands because fewer and fewer people are able to clearly attribute content they choose to its original publisher (and I’m not even mentioning author recognition here—it’s lost in the process).

Two, Facebook has become a giant filter: roughly 10% to 20% of a publisher’s output that is pushed into Facebook actually ends up in user’s newsfeed—even if she subscribed to it.

In its dealings with the media industry, Facebook has acted in a rather twisted way.

First it lured thousands of publishers to its Instant Articles system, a well-designed setup that yields super-fast access for mobile users and, of course, vast audiences. It eventually triggered a response from Google, called Accelerated Mobile Pages (see our coverage here). Unlike Instant Articles that run within Facebook’s walled garden, AMP is an open platform.

Unfortunately, once scores of publishers became hooked to Instant Articles’ huge traffic, Facebook decided to squeeze the pipe by narrowing the volume of news it delivers to users’ newsfeeds. It was a “pure” business decision: FB found out that people shared more friends and family contents than news that might be read but not shared. That doesn’t work for the Facebook advertising machine that needs a constant recirculation between pages. Details are here.

As a result, publishers ended up losing on both ends. They allowed a massive leakage of their content viewership and, as a reward, got hurt by Facebook’s commercial decision to alter its algorithm to the detriment of news.

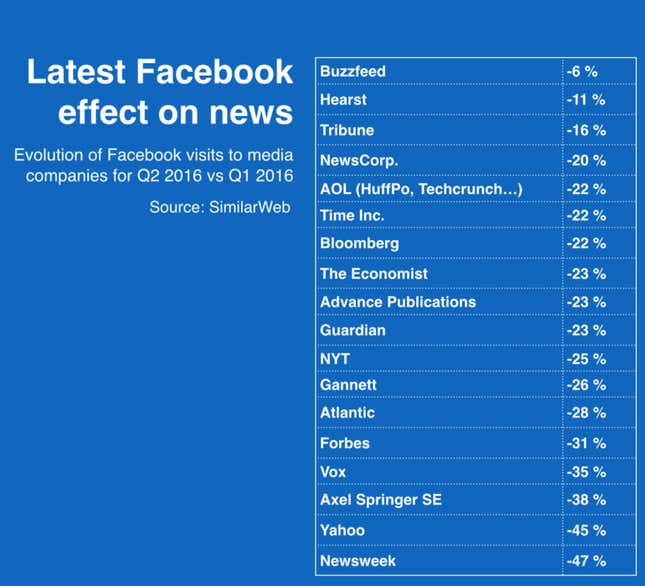

Last month the analytic firm SimilarWeb issued a compelling report that shows the impact of Facebook’s decision:

Publishers don’t like hearing me say it, but they bear a share of responsibility for their predicament. Eager to accumulate the largest possible amount of eyeballs (regardless of their actual value), driven more by panic than by a thorough analysis, publishers preferred being wrong with the crowd rather than taking the risk of being right alone. They flocked to the Facebook ecosystem, and spent large sums for tools, dedicated teams, and snake-oil consultants. Forgetting the damage once caused by the RSS frenzy (another powerful content leakage), they doubled down with Facebook, on a much larger scale.

Today, publishers around the world have switched on the whining machine, denouncing Facebook’s cynicism and begging for more respect from the giant social network.

I won’t bet on their chances to get anything more than cosmetic alterations. Not because Facebook is in any way devilish, but because it doesn’t give a damn about journalism or the publishing industry. Both are a tiny speck in its galaxy and certainly not the one carrying the best advertising revenue.

Since it doesn’t make any sense business-wise, I bet Facebook will never invest in a first-class editorial team.

Jeff Jarvis and others might, with good arguments, call for Facebook to get an editor, but I don’t see it happening.

The explanation for Facebook’s total lack of regard for news lies in its ingrained insular culture.

It boils down the following: A blind-faith in the algorithm’s superiority over the human process (often invoked in the name of “scalability,” an obligatory buzzword here), and certitude of its intellectual superiority over, roughly, the rest of the world.

All of it is wrapped in a certain condescension toward the journalism profession. I have felt it ever since I first visited the Valley, and I have experienced it even more acutely as I’ve moved here for my JSK Fellowship at Stanford: The tech elite maintains a strong disdain for journalism in the traditional sense. (The only notable exception is Google, whose management shows a genuine concern toward the degradation of the news ecosystem—even if public affairs considerations are never far-off).

Technorati tolerate complacent bloggers who are easily controlled through access and cajoling, but I don’t think that someone like the Wall Street Journal’s John Carreyrou, who unveiled the Theranos scam, enjoys the respect he deserves. (On the subject, see Nick Bilton’s recent piece in Vanity Fair and also Jean-Louis Gassée’s personal account in the Monday Note.) After all, Carreyrou did break the dream of an historic disruption in blood analysis embodied by a charismatic Silicon Valley lioness.

Facebook’s self-centric, we-know-everything culture also percolates in the way it delegates decisions to its “ROW” (Rest of the World) representatives. In this case of picture censorship, the whole chain of command ended up on the desk of a poor soul somewhere in Hamburg who was in charge of supervising contents for Nordic countries. This person and his/her supervisors might have had the cultural background of a cabbage—no one really cared at FB’s headquarters in California. All they were asked for was to play by the book. This a big problem. Facebook is caught in a major contradiction when it comes to distributing information.

On one hand, as Quartz reported last April:

“We are a tech company, not a media company,” Zuckerberg told university students in Italy, after he was asked whether the company planned to become a news organization. “We build the tools. We do not produce any content,” he elaborated at Rome’s Libera Università Internazionale degli Studi Sociali.”

But three years earlier, here is what he had say:

Our goal is to build the perfect personalized newspaper for every person in the world. We’re trying to personalize it and show you the stuff that’s going to be most interesting to you.

In Zuck’s parlance, “personalized” means having the job done by a machine—to the extreme sometimes, like when a few days ago, Facebook’s trending topics surfaced yet another 9/11 conspiracy theory. It actually happened a few weeks after the company fired its skeletal staff of junior editors—all of them were temps, of course—they couldn’t be granted the salaries and perks of the company’s prized algorithms designers.

At some point, Facebook will have to admit that it actually is a media company.

It will also have to revisit its puritanical approach to the news, and its Alice-in-Wonderland vision of an information pipeline that favors a positive vision of the society.

Facebook’s position as the world’s dominant editor implies great responsibilities. So far, these haven’t been handled well.

This post originally appeared at Monday Note.